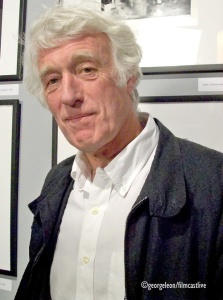

ROGER DEAKINS, KEEPING AN EYE ON THE SMALL THINGS

Roger Deakins sat down with NPR's Melissa Block for an interview at his Santa Monica home. As twilight fell, they watched two of the cinematographer's favorite scenes — from No Country For Old Men and The Shawshank Redemption — and talked about how the play of light and shadow helped him shape each shot.

Roger Deakins' least favorite phrase? "We'll fix it in post." "It's one of the worst expressions to come into the industry," says the veteran cinematographer, an eight-time Oscar nominee who shot The Shawshank Redemption, A Beautiful Mind and every Coen Brothers movie since Barton Fink. Digital post-production tweaks — everything from subtle cleanup to the deletion of geographical features and the insertion of thousands of computer-generated extras — are increasingly common in modern moviemaking. "If it's used correctly, it's a fantastic technique," Deakins tells NPR's Melissa Block. In fact, in Jarhead, which Deakins shot with handheld cameras in a California desert, director Sam Mendes wanted "this flat, surreal landscape, emptiness, the horizon going into nothing," Deakins remembers. So, in post-production, the mountains that had actually loomed on the horizon were digitally erased.

Better yet: In the Coens' O Brother, Where Art Thou?, there's a scene where a car full of convicts hits a cow in the road. The sequence was convincing enough, Deakins recalls, that animal-cruelty watchdogs cried foul. The filmmakers invited the activists to visit the Digital Domain special-effects lab, "and the effects guys had to show them through the stages of how they'd animated this cow so it looked like it had been run over by the car." Still, to a man like Deakins — an avid still photographer, and a connoisseur of "the little things" like the quality of light or the angle of a shadow — an over-reliance on post-production magic is anathema.

"There are certain things you can't fix in post, certain things that would no longer look organic if you did it in post, really," he says. "It's one thing removing a mountain in the background of a shot; it's another thing adding 15,000 people and changing somebody's face. That kind of manipulation, I think, gives itself away eventually. ... And that's when you lose an audience." Deakins says what's essential, at least in his filmmaking philosophy, is remembering that the big things and the little things alike — "the camera style and the lighting ... the imagery and the photography and the effects" — are there to serve the movie's characters and story. He cites The Shawshank Redemption* as a case in point.

"A lot of people say it's nicely photographed, and I think it is," he says. "And I think it's the simplicity that makes it well photographed. ... It's not like these are necessarily fantastic images; it's really about the content. It's not about making great images." "I like simplicity," Deakins reiterates. When he's lighting a scene, especially, "I like using natural sources.

I like images to look natural — as though somebody sitting in a room by a lamp is being lit by that lamp." In a film framed by such a naturalistic vision, Deakins insists, attention-getting gestures have to be especially well thought out. "When you move the camera, or you do a shot like the crane down [in Shawshank] with them standing on the edge of the roof, then it's got to mean something," he says. "You've got to know why you're doing it; it's got to be for a reason within the story, and to further the story." "There's nothing worse than an ostentatious shot," Deakins argues. "Or some lighting that draws attention to itself, and you might go, 'Oh, wow, that's spectacular.' Or that spectacular shot, a big crane move, or something. But it's not necessarily right for the film — you jump out, you think about the surface, and you don't stay in there with the characters and the story."