“I’m Mexican”. A Magical Realism Auteur Memorable Response.

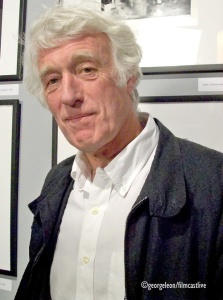

After an emotional Best Director acceptance speech for the “Shape of Water” at the 2018 Golden Globes, reporter Julia Pierrepont of China’s Xinhua News Agency asked him how he balances the darkness and terror in his often monster-filled films with “the joyful and loving person” that he is. Del Toro’s response was simple: “I’m Mexican.” But this answer wasn’t only about his nationality, but also about his vernacular culture. Understanding Mexico’s illustrious vernacular culture is understanding Guillermo De Toro.

Since his humble beginnings, Guillermo has been an eloquent speaker, shaped by age and experience into not only a successful auteur but an engaging educator. His scholarly conversations—much like the narratives of his films—are seasoned with a unique brand of vernacular folklore that he famously attributes to his Mexican identity.

His intellect is a vibrant tapestry woven from his country’s rich cultural legacy: the revolutionary muralism of Diego Rivera, the surrealist spirit of Luis Buñuel, (an Spaniard, but established a style of "surrealist realism” in Mexican Golden Age of Cinema), the provincial narratives of Emilio 'El Indio' Fernández, the haunting symbolism of Frida Kahlo. By bridging the mysticism of Juan Diego with the visceral traditions of The Day of the Dead, and his fascination with the afterlife haunting stories, Guillermo enlightens his audience on more than just the cinematic arts; he reveals the profound parallels between the magical realism trope and the daily realities of the human condition.

Guillermo De Toro has called Frankenstein his "Mount Everest"— here is why is so significant:

1. The "Beautiful Monster" Philosophy

Most directors treat Frankenstein’s creature as a horror movie prop. Del Toro, however, views monsters as patron saints of the imperfect. * The Scientist's Perspective: He understands the "entity" not as a villain, but as a "displaced soul" seeking purpose. The Parallel: Just as he did with the Amphibian Man in The Shape of Water, Del Toro will likely focus on the creature’s profound loneliness and intellectual curiosity, rather than just the "lightning and stitches."

2. The Influence of European Romanticism & Mexican Muralism

Shelley’s novel is steeped in the "Sublime"—the idea that nature is beautiful but terrifying. Del Toro is the perfect entity to capture this because he blends, Bernie Wrightson’s Art (Del Toro is a devotee of Wrightson’s intricate, "Baroque" illustrations of the monster) and Mexican Sentimentality, he infuses the creature with the "visceral emotion" . It won't be a "quiet" monster; its grief and its joy will be maximalist and big—because he is Mexican.

3. A Critique of the "Creator"

In Shelley's work, Victor Frankenstein is the true failure—an irresponsible "parent" or scientist. As a scholar-director, Del Toro often critiques authority and father figures (as seen in Pan’s Labyrinth and his Pinocchio).The Entity's View: He frames the creature as a "miraculous accident" and Victor as the cold, modern man who lacks the "mysticism" to understand what he has made.

4. The Visual Architecture

For Frankenstein, he moves away from the "flat" laboratory look and toward something that feels like an ancient, gothic anatomy sketch come to life.

With Del Toro at the helm, the "Frankenstein Entity" it’s no longer a figure of fear, but a mirror of the human condition. It’s a story about the tragedy of being "crafted" by another, much like how he feels his own identity was crafted by the legends of Mexico. He, Del Toro has often said that Pinocchio and Frankenstein are the two stories that defined his childhood—not as separate tales, but as two sides of the same coin. He views them as a "Father Trilogy" (alongside his film Nightmare Alley), exploring the "lineage of pain" passed from creator to creation.

Here is How He Weaves These Two Together:

1. The "Unholy" Mirror

In Del Toro’s eyes, both characters are "entities" thrown into a world they didn't ask to join, created by fathers who are grieving or ambitious. Pinocchio is a wooden boy carved from a tree growing over a dead son's grave—death literally giving way to life. Frankenstein’s Creature is a "mosaic" of the dead, reanimated to satisfy a scientist's ego. The Link here is that Del Toro treats both as "perfect innocents" or "blank canvases" who are ultimately more human than the men who made them.

2. Disobedience as a Virtue

This is where his "Mexicanidad" and revolutionary spirit shine. In traditional versions, Pinocchio is "good" when he obeys and "bad" when he lies. Del Toro flips this: He believes disobedience is a virtue. To him, Pinocchio and the Creature only become "real" when they stop trying to please their "fathers" and start making their own choices. He famously said he didn't want Pinocchio to turn into a "real boy" at the end because he was already real in his flaws and his wooden skin. He applies this same grace to Frankenstein's monster—he is "perfect" exactly as he is, stitches and all.

3. The Religious & Catholic Weight

As in the mysticism of Juan Diego religious story, Del Toro’s work is deeply "Catholic" in its imagery. He views the Frankenstein monster as a "Messiah figure" who expiates the sins of his father (Victor).In his Frankenstein, he even echoes the "Father/Son/Holy Spirit" dynamic, framing the creature’s suffering as a form of grace. Both films use religious symbolism (like the crucifix imagery in Pinocchio) to show that "monsters" are often the most saintly figures in a room full of "normal" men.

4. The Biological vs. The Artificial

While Pinocchio is wood and the Creature is flesh, Del Toro treats them as brothers. Pinocchio represents the soul's ability to inhabit a "static" object. The Creature represents the soul's struggle within a "broken" body. Both are "maximalist" in their emotions—they don't feel small feelings; they feel everything with the scale of a Greek tragedy.

“To be is to suffer. But to be is also to love. It is the same thing, whether you are made of flesh, or made of wood." — Guillermo del Toro