Shown in three parts for theatrical release, the first part is ninety eight minutes long and not a second seems wasted. With the film moving from one international locale after another, at such a pace and without one slow moment it seems inconceivable to produce a two and a half hour version of the film for a television format.

Carlos was shot in 9 countries, spanning three continents and using the 11 languages of the playing characters, including Japanese, Russian, Hungarian, French, English, Arabic and Carlos’s native Caraqueño (Caracas accent) sounding Spanish sprinkled with conspiratorial whispering, audacious gunplay and Marxist dialectics.

One is left with the impression that one could sit forever holding on as the plot careens ahead. Edgar Ramirez the versatile Venezuelan born actor plays the part of Carlos, the Venezuelan-born terrorist Ilich Ramirez Sánchez, who became a member of the leftist Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) and whose nom de guerre gives the movie its title. Edgar Ramirez plays Carlos with such “revolutionary internationalist” conviction that the critics compare him with Brando since the film was premiered at Cannes early this year.

The film was entered in competition in Cannes but it was relegated by the jurors to the official program due to it cross platform. ”A made for TV Movie” and it’s financing by Studio Canal+, and conceived as a three-part television mini-series could not be counted as cinema, but by shooting the film in 35 millimeter negative stock and framing it with 2.35:1 aspect ratio (Cinemascope), Olivier Assayas ensures that the film does not resemble a just a “made for TV movie”. The use of hand held camera and other well placed camera movement as well as the intermingled editing provides a sense of time and landscape as well a sense of scale and depth that are all very cinematic.

The second part (106 minutes) shows Carlos as a seasoned leader of an internationalist organization that sees itself as the vanguard of a struggle against imperialism, Zionism, and whatever evil–ism catches its fancy. Their revolution, of course, never happened, but what was sometimes called “the Carlos Network” or “the Carlos Group” was nonetheless in the vanguard of future developments. Most of it centers on the unbelievably daring kidnapping of the oil ministers attending an OPEC meeting in Vienna in 1975 and the gunning down of two French officers in an apartment on the Rue Touillier in Paris and of a former colleague of his from the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (P.F.L.P.) which serves as dramatic centerpieces in Assayas’s movie.

The last part (115 minutes) focuses on an anticlimactic finale with an overweight, bloated, yet still narcissistic Carlos who wanders errant looking for a place to call home, hindered by both, his past mistakes and a radically different world accentuated by the fall of the Berlin Wall and the abandonment of his backers to be finally captured by the French DST in Sudan.

The oddest thing about the film is the music. Totally anachronistic, at first it feels like an empty device. Suddenly, to the tune of Missing Boys and New Order, the world of international terror takes on the appearance of an MTV behind-the-scenes moment. One of Assayas’s better tongue in cheek moments, we are left with the impression that perhaps our boy wonder sees himself as a gun wielding rock star and this is his soundtrack.

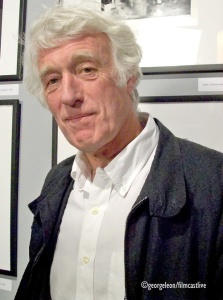

Carlos's widescreen dexterity and aesthetic vision by Assayas are crafted for viewing in a theater. The cinematography by Denis Lenoir, AFC ASC and Dan Franck are both powerful and agile with a few stylistic flares such as retro 70’s production design and lighting. Assayas relies heavily on close-ups, probably on account of the film's mini-series origins. These enhance the closeness and accentuate the small size of the terrorist cells in comparison to their global enemies. Also, the proximity to the characters offers close-ups to their behavior and intimacy which adds to the feeling of being present.

seen either version, he did issue vaguely menacing

challenges to its accuracy in the weeks leading up

to its big-screen debut at the Cannes Film Festival in May.

Carlos is definitely an epic worth watching in all of its five and a half hour glory. From the variety of filming locales to the extensive historical references, not a moment seems superfluous. Most films mercifully end after ninety minutes; Carlos could have been a little longer.