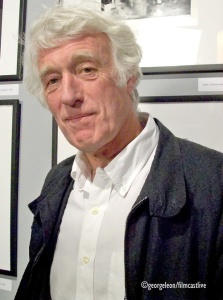

EXPOSURE: RIDLEY SCOTT

Ridley Scott’s extraordinary sense of visuals was clear from the start. In 1977, he made a big splash in the film industry with The Duellists. Based on a Joseph Conrad story and set in the Napoleonic era, the film was nominated for the Palme d’Or and earned Best First Work at the Cannes Film Festival, and BAFTA and BSC nominations for cinematographer Frank Tidy, BSC. For Scott, it was a case of an overnight sensation, a dozen years in the making: the filmmaker, who grew up in a military family and possessed an M.A. in graphic design from the Royal College of Art, had already revolutionized the advertising industry, having directed thousands of television commercials dating back to the early 1960s.

Scott brought an artist’s eye and a storyteller’s passion for detail to the craft of selling with images, and his first stab at the big screen turned out to be a harbinger; his next film, Alien, changed the sci-fi genre, if not the entire film industry, forever. Scott followed that up with Blade Runner, one of the most influential films in cinema history in so many areas, first and foremost its cinematography by Jordan Cronenweth, ASC. Right through to his newest work, Robin Hood, the director/producer’s work continually displays the scale and grandeur of epic cinema. David Heuring caught up with Scott to probe his thoughts about cinema lighting, his roots in commercials, and his feeling about new digital technologies. (Hint: if the term “old school master” comes to mind, Scott would brook no quarrel.)

Robin Hood is your fifth film with John Mathieson, BSC. What appeals to you about his work? Scott: John and I worked together for the first time on Gladiator. I had seen a film called Plunkett & Macleane, which John had done for my eldest son, Jake, and I thought it was beautifully done. Time literally is money in film, particularly today. I come on the set knowing exactly what I want to shoot. That comes from my experience in commercials. You have to hit the floor at 8 a.m., and you’d better know what you want by 8:30. You can’t stand there and talk about where to put the camera. That is true in features as well. No matter how big the budget is, it’s never big enough. The clock is always ticking. And John is fast, and artistic in a good way. He has got great taste.

You directed more than 2,000 commercials prior to your first feature film. How did that impact the way you see things? I learned everything from commercials. RSA (Ridley Scott Associates) is 41 years old this year, with many great directors and good talent. I was making commercials in New York in 1965 when they brought us in to get what was called the ‘English light.’ But when I was starting off with the BBC, I couldn’t ever get the bloody sets lit properly. I used to be very critical. I thought commercials looked awful. The interiors were always lighter than the exteriors. It looked completely ridiculous. When I was getting into commercials, some of the people I encountered did not take them seriously. They were taken as a drudge. And the difference was that I took commercials very seriously. I loved every moment of the 20 years I was passionately engaged in television commercials.

Derek VanLint (CSC), who did my second film, Alien, must have done at least 100 commercials with me. Frank Tidy (BSC) did The Duellists, and probably 150 commercials with me. I think I can safely say that what we did (in commercials) has changed the way feature films look today. That includes lighting, as well as editing. Do I need to see the hand go on the door handle, the feet going up the stairs? No. Communication in television is a story in 30 seconds. That’s why it’s harder frequently for a feature film director to move back and try to do television commercials. It’s hard to grasp that language. For a television commercial director to suddenly be given two hours to tell and pace a story – that can be difficult as well.

How did you explain your vision for Robin Hood to Mathieson and your other collaborators? You start by going down to the root. With a legend like Robin Hood, you have to decide whether he was real or not. And in this instance, we’re making him a real guy. This is not Lord of the Rings. He is a shaker and a mover against the rights and wrongs of the Crown. And you must decide what time in history to pin it to, and I notched it down to the moment of the death of Richard Coeur de Lion (Richard I, a.k.a. Richard the Lionheart) who in 1199 is returning home after 10 years in the Crusades. He is bankrupt, collecting old debts as he travels through France. In the first eight minutes of the movie, we see Richard, the great man, die. In his army was a man called Robin Longstride, a yeoman bowman who becomes Robin of the Hood.

How did your aesthetic choices grow out of that story? It’s taste. It starts off with a rug on the floor, the food they eat, the furniture they sit on, or the illumination they are going to get through the windows. If you are in a beautiful 11th century room, you want to have that illumination. You stand in the location. We started shooting in January, so it was grim and beautiful. I knew the valley at Guilford like the back of my hand, because we’d shot there for Gladiator. After landing in the U.K., from that moment on the trees become deciduous, and we are going into spring. I managed to get all the forests within a 40-mile radius of London. Everyone is short of money, so forests that had never been filmed in, like Windsor Great Park, were opened to me. There are 800-year-old trees there. At first, we caught a bit of spring and the leaves hadn’t gone too thick, so we could use natural lighting, and the fast film stocks helped. Then, the leaves became way too thick and that was tough for John, requiring constant fill light. For the interiors, we had huge sets, many of which were built at Pinewood-Shepperton. I was very much leaning in the direction of the painter Pieter Bruegel. Ironically, Bruegel didn’t come along until about 300 years later, but when you look at his work, it looks like the Dark Ages.

Most of your films are framed in a widescreen 2.4:1 aspect ratio. I always feel that when a film opens up and it’s wide, it’s kind of nice. I don’t do anamorphic. Alien was anamorphic and it was a nightmare for focus. It was the relatively early days of the anamorphic zoom lens. My focus puller in those days was Adrian Biddle (BSC). He recalibrated the lenses one weekend because for some bizarre reason they were forward-focusing. We couldn’t work out why; it would look sharp through the camera. Today, we tend to use Super 35 spherical, which is faster and easier to keep sharp.

Have you tested any of the latest digital cameras? Not really. You have to watch that the tail of science shouldn’t wag the dog of creativity. You don’t have to consult with a science book simply because you have adjusted to digital or 3D. I know digital is not as straightforward as it sounds. I know it is not a case of ‘you don’t have to light anything’ - that is rubbish. You’ve got to pay as much attention to digital as you pay to film cinematography. With film space and digital space, the film will tend to be more subtle in certain areas. In a way, it’s more cosmetic without getting into what I call ‘the plastic zone.’ I appreciate the consistency that digital prints and projection bring, and I’ve embraced digital in the grading, because it means I can do it more swiftly.

How did you use DI tools on Robin Hood? I am a painter. Not first and foremost, but I had an elongated time - seven years – in art school, so I can draw, and I use my eye that was evolved and refined in art school. That’s true even more so today than ever before because I can literally go in and examine a frame and say, ‘In the middle ground, I want all the twigs on the ground to be sharp.’ You can assess it as an individual picture. We’ll do the first minute of a scene, and then I leave Stephen (Nakamura at Company 3 in L.A.) to do a lot of the work, and I come back and check. If you have a good grader, it means you can move faster. I probably graded Robin Hood in the space of two weeks. We worked on a large screen, and it’s beautiful and subtle. You can get a really great transfer off the film. I love the sharpness of 4K for this type of material. But half the time I’m trying to attain the beauty of that back in the digital space, and you can’t. It’s just different. For certain things it just will not go the whole nine yards.

What are your memories of working with Slawomir Idziak (PSC) on Black Hawk Down? I look at a lot of low-budget movies because they display emerging talents, which are always very interesting. I have a great admiration for (director) Michael Winterbottom, and he had done a very interesting film in England called I Want You, which Slawomir had photographed. We met, I asked if he wanted to do Black Hawk Down, and away we went. I remember him standing in Morocco and saying ‘God, I hate sunshine.’ I said, ‘Well, I’m afraid you are going to get a lot of sunshine here.’ When you’re in England or Ireland, there is fairly constant precipitation and water in the air. It’s misty more often than not, and there isn’t that harsh sunlight. So there is a beauty in the Irish and English weather and it’s the best thing for skin tones. Being Polish, Slawomir loved the Polish light, which is all bloody drizzly! But Black Hawk Down is a special-looking movie.

What are your recollections of working with Jordan Cronenweth (ASC) on one of the most influential films in cinema? Blade Runner was tough for Jordan because at that moment he was really quite ill. It was a chance I took because of the guys I’d seen in the U.S., he was the man. He’d done a film I really liked the look of called Cutter and Bone (U.S. title: Cutter’s Way). I met with him and just liked him. At the time, I had done 2,000 commercials and The Duellists, which got a prize at Cannes, and Alien, a pretty big blockbuster. So, I was probably the most experienced new kid on the block! Then there was a baby of mine called Blade Runner. I was 42 or 44 years old, and I was used to a certain kind of autonomy. To explain the world constantly started to get really annoying, and I must say that I became a bit of a beast because that was the only way to get it done. Jordan was great because he could argue. We had some really great, pretty fruity arguments. He was feisty and just fantastic.

International Cinematographers Guild