by Bob Fisher

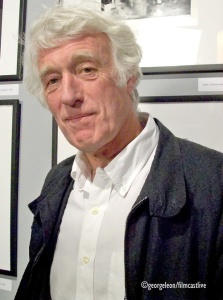

“I thought it was a beautifully executed film that was clearly produced with limited resources,” recalls Nolan. “I had to meet the guy who shot it.”

About a year later, Nolan called Pfister and introduced himself. Pfister was shooting a low-budget film in Alabama. Nolan mailed him a script. After reading it, Pfister caught a 7 a.m. Sunday flight to meet Nolan in Los Angeles.

“I decided during our first conversation that I wanted to work with Wally,” Nolan says. “There is a synergy that affects our ability to translate ideas into images. It’s the sum of those images that leave a lasting impression rather than the individual shots.”

They made a verbal agreement to collaborate on Memento.

“Chris is a brilliant director who is sensitive and collaborative,” says Pfister. “He gave me the freedom to light the way I had always wanted. We shot about 25 percent of Memento in black and white with dark, contrasty images and worked with the production designer, to get interesting textures. We took it to the next level with Insomnia.

Their next collaborations were Batman Begins and The Prestige. Pfister earned Oscar nominations for both films, while Nolan was lauded by critics and audiences. While they were still shooting The Prestige, Nolan informed Pfister that people at Warner Bros. were talking with him about a script that he and his brother Jonathan and David Goyer had co-authored for another Batman movie. After they completed production of The Prestige, Nolan gave Pfister the script for The Dark Knight.

The Dark Knight is a fast-paced, adventure story set in Gotham City with all the familiar characters and a new villian, The Joker. Nolan said the studio planned to augment worldwide distribution in 35mm anamorphic format by premiering The Dark Knight on more than 100 IMAX screens.

Nolan also had an idea for producing the opening six-minute scene where the audience meets the Joker in IMAX format. The 65mm film would be “rezzed” down to 35mm anamorphic format for release to traditional cinemas.

Neither Nolan nor Pfister had ever shot a frame of film in IMAX format, but that didn’t stop them. They embraced an opportunity to explore a new frontier. The IMAX frame is 65mm wide and 15 perforations long, and it is composed in 4:3 aspect ratio. The image area is 10 times larger than a 35mm anamorphic frame.

They spent an afternoon and evening shooting tests with an IMAX MSM camera in the backyard and garage at Nolan’s home in Los Angeles. The camera weighs around 65 pounds and can be used on a Steadicam and an Ultimate arm.

“We wanted to see how the camera handled, and also experimented with composition, lenses and exposing the negative in different ways,” Pfister says. “Afterwards, we put the camera in the back of a pickup truck and shot a night test in practical light while we were driving down Sunset Boulevard.”

Nolan and Pfister envisioned the possibilities for creating a more immersive moviegoing experience when they saw the test footage projected.

“There was no visible grain, and we could see every detail in the darkest shadows with truly rich black tones and extraordinary contrast,” Pfister says.

After discussing the possibilities with Pfister, Nolan decided to produce about 30 minutes of car chase and other action scenes, aerial shots and physical effects in IMAX format. The producers and executives at Warner Bros. supported the decision.

Nolan also envisioned a new visual grammar for The Dark Knight.

“The Batman movies have always been dark,” Pfister says. “The Dark Knight has its dark elements, but there is a lot of daylight and other scenes in bright environments, including office settings with flourescent lights and big open rooms with sunlight streaming through windows. Chris felt that the drama would have more visual impact if we saved the darkest imagery for the end of the film.”

Nolan was always around the camera with the actors rather than in a video village while they were shooting. He trusted Pfister and his crew to capture his vision on film.

“Batman is a creature of the night,” Pfister states. “There is some sheen on the cowl and the rest of his costume, but his cape is absolutely matte black. It was like lighting a piece of Duvateen. We used eye light to bring the person behind the mask to life. I used a Kino Flo Kamio ring light on an armature attached to the camera. If the light was too bright, I used an ND6 gel and a quarter CTS filter to warm it up. It didn’t create shadows, because it’s a soft light, but it was hard enough to put a ding in his eyes.”

The great Swedish cinematographer, Sven Nykvist, ASC, observed that the eyes can reveal the souls of human beings. The “ding” that Pfister put into Batman’s eyes helps the audience make an intimate connection with him by revealing his feelings.

There are no CGI or other digital effects in this action-packed film. All of the action unfolds in front of the lens. Nolan also opted for traditional optical rather than digital intermediate timing. The nuances in looks were recorded directly on the negative.

“Some people say that’s old-fashioned,” admits Nolan, “but Wally and I agreed that it is a more natural look and organic feeling that is right for The Dark Knight.”

The moral of this story is that artful moviemaking is a collaborative process for Nolan and Pfister. Their journey continues. What will they do for an encore?